Earthaven Ecovillage Podcast

From Permaculture to Regional Mutual Aid with Zev Friedman

From Permaculture to Regional Mutual Aid with Zev Friedman

Broadcast March 29, 2021

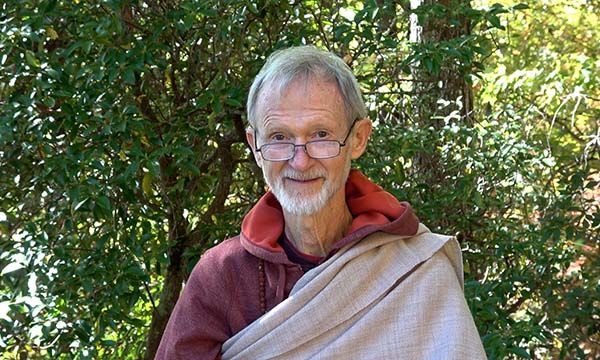

Featuring: Zev Friedman and Diana Leafe Christian

In this podcast, Zev Friedman shares how he started living and teaching permaculture at Earthaven Ecovillage, and then how that led to forming Co-operate Western North Carolina (Co-operate WNC). Along the way, Zev shares examples of different types of permaculture and the work that Co-operate WNC is doing.

Listen Here

Recent Earthaven Ecovillage Podcast Episodes

On Storytelling with Doug Elliott

My Journey with Natural Building with Mollie Curry

Creating Culture and Community Through Ritual with Kaitlin Ilya Wolf

Mentors, Elders, and Groundhogs with Doug Elliott

Healing People and the Planet with Swami Ravi Rudra Bharati

What Earthaven is All About… For Me with Paul Caron

From Permaculture to Regional Mutual Aid with Zev Friedman

Nature Connection with the Academy for Forest Kindergarten Teachers

Compassionate Communication in Community Settings with Steve Torma

Finding Community with Diana Leafe Christian

Life in Community with Steve Torma

Lessons from a Life in Community with Lee Warren

From Permaculture to Regional Mutual Aid with Zev Friedman TRANSCRIPT

From Permaculture to Regional Mutual Aid with Zev Friedman TRANSCRIPT

Earthaven is my own personal greatest training ground for cooperative living, because what we’re doing here is mutual aid. So to be able to be here and learn those lessons in a day-to-day way and then apply them to a larger social context has been a real honor and gift.

Hello, everyone, my name is Debbie Lienhart from the School of Integrated Living at Earthaven Ecovillage. Welcome to the Integrated Living Podcast, where we explore integration within ourselves with the people around us and with the planet. In this episode, host Diana Leafe Christian talks with Zev Friedman.

Hi, Zev.

Hi, Diana, would you please tell us your whole name and introduce yourself as a person here at Earthaven and who teaches for SOIL?

I would be happy to.

My whole name is Zev Hayim Segal-Friedman and I live here in the Hamlet neighborhood at Earthaven. Very happy to say that. And I grew up here in Western North Carolina, one of the few people I know who lives here, over in Silva in Jackson County in a four-acre kudzu patch, where I moved with my parents when I was two years old in 1983. And I’m now running an organization called Co-operate WNC, which is a regional mutual aid network.

What does WNC stand for?

Western North Carolina.

So your organization is Co-operate Western North Carolina.

Right.

And what does it do?

It’s a regional mutual aid network. We coordinate different informal community groups, organizations, and households to cooperate and share resources and knowledge and develop long term relationships for a regenerative future.

So you are a permaculture teacher, you teach it, you design landscapes. You’ve been doing this since before you came to Earthaven in 2013. You’ve taught it here before you moved here.

That’s true. Taught it here since then.

Can you tell us how you moved from teaching permaculture and designing landscapes to Co-operate WNC?

Sure. So we’re going to take about six hours now, right?

No, we’re going to take it a little chunk at a time.

Okay. Yeah, well, to really answer that question, I have to go back to how I got into permaculture itself, because permaculture is really a strategy for me. To meet kind of a long term sense of mission and purpose that I developed in my own life when I was starting around when I was 17, but also with my parents because I grew up in a social activist family and kind of got these values of examining how we are human and what we’re doing here at an early age.

But then when I was about 17, I started to have experiences myself that led me to both witness the beauty of ecosystems and human cultural diversity on the planet and also feel the grief of loss and destruction of those systems and peoples and places. And I began to recognize I wanted to be part of keeping the beauty alive and slowing the destruction down. And so I started seeking then for ways to do that. And permaculture was was the best thing that I came upon.

Why is that? What is it about permaculture? Did its basic principles or practices drew you to it in order to fulfill those values?

Yeah. Well, I think that one thing is I was in the environmental science program at UNC Asheville, and there are all these academic formalized approaches to dealing with environmental problems, and they were very nonintegrated and non-grassroots. And permaculture I came to understand as a very people-owned approach to earth healing and cultural healing, something that we can actually do with community control at a community scale.

Could you tell our listeners the basic what it is, how it works of permaculture to give a basis for where else we’re going to explore in this talk?

There are a lot of different definitions coming from different directions. But one definition I like is from my old mentor, Chuck Marsh, who used to live at Earthaven. He has now passed. He was my business partner too, and his definition was permaculture is a design system for creating regenerative human habitats. And I like that because what that emphasizes is it’s a design practice. It’s a way of looking at any system, whether it’s an economic system or a landscape or a business or a family or a community, and using a certain set of design principles and approaches based in ethics, which people care and earth care and sharing the surplus, and then design that system based on a set of ecological principles.

Could you say more about why people tend to associate permaculture with gardening and give some examples of applied permaculture design in some of the areas you just mentioned?

Yes, well, I think that in the U.S., because permaculture is a global movement and by the way, really closely tied with the agroecology movement, which is more owned by people of color and indigenous people around the world, permaculture has tended to be a pretty white movement. But in the U.S., I think it’s come to be associated with gardening. This is actually related to your original question of why Co-operate WNC and why mutual aid, because we have a very fragmented society in the U.S. and the types of change that we need, in my opinion, to have a really regenerative human future are so deep that most people who are in privileged positions aren’t willing to consider that type of change.

And so gardening, something that’s just a gardening system, is an easier bite to swallow for a lot of people. Oh, I can just change the way I manage plants. But actually, permaculture is about redesigning the entire human approach to life.

So white people in general, in your experience and the experience of permaculture designers in the U.S. Are more willing to look at the oh, let’s garden in a different and better way aspect of permaculture, then all the aspects which you and your colleagues are wanting more people to take a look at.

Yeah, I think so. And because the other aspects ask more challenging questions of us and make deeper transformational demands for our lives and our communities. And so, yes, I think that’s true. And I’ll say, though, that things like the COVID-19 experience that we’ve just been through as a society and other emerging crises are putting some cracks in that and causing more people to consider deeper types of change. So that’s opening up more of a more of a pathway for the kind of social and economic transformation that I think has also been a part of permaculture from the beginning.

Could you give some examples of applied permaculture design, say, first in economic or social realms in the United States. Just pick one and then you could tell us some applied design and then maybe the other, because I’m betting people can picture permaculture-designed gardens, but they may not yet be picturing what you know about.

Yeah, and that’s another thing I’ll say is that is it’s easier for us humans to imagine what we can see. And so that’s another reason why gardening has been the more adopted layer of permaculture. So I do think of the landscape systems as a training ground. If we can see the interconnection between plants and fungi and animals and water systems, it makes it easier for us to think about the interconnections between human communities and so on. So your question examples.

I’ll speak first to kind of a visible, tangible ecological example, one that a lot of home gardeners are working with is if you have chickens or ducks. You can design the system around them where the chickens or ducks are integrated in a run along the edge of your property, for example if you have an invasive plant problem coming in from the edge, you can create a long, skinny run along that edge with fences on both sides.

And the chickens, especially chickens in this case, patrol that and they scratch things up, dig up the roots of the plants that are trying to come in from the edge and can act as a biological control. Then you can plant elderberries and mulberries. In that run, the elderberries and mulberries shade the chickens, which keeps them more comfortable in the summer. They provide fruit for people, they drop extra fruit for the chickens, and then you can put wood chips around the mulberries and elderberries and dig shallow pits so that when heavy rains come, you fill those pits with wood chips inoculated with a certain mushroom species and the rain percolates into those pits, feeds the plants, filters the water, makes edible mushrooms, which also make food more food for the birds.

And so it’s an integrated system that includes animals, fungi, and plants in an interconnected food web that makes more yields and health than any of those things, would alone.

So the combination, which is the permaculture design of this particular home site from invasive plants strategy, not only does that, but it provides you with mulberries, elderberries, edible mushrooms and eggs and chicken meat, if you are an omnivore, and water filtration and you have fun creatures to look at. And the manure that you can use in your compost bins to create compost with.

Thank you for that example.

So then going to a social example, I’ll give one from my own work because that’s what I’m most familiar with. In 2011, we determined that permaculture design classes, which were what a lot of us have been teaching, are these big 16 or 20 day classes that are a big commitment and expensive for people to join. And a lot of people are saying, I can’t sign up for that. So we did a big survey, my colleagues and myself, and took feedback on what would help and people said we need something cheaper and we don’t care about certification.

And so what we actually did, we went back to the drawing board and we said, all right, where are the different groups that could be matched up and make this work? And we came up with was this thing called the Permaculture in Action Class, where we teamed up with land owners who we had done permaculture designs for, and they paid into the class. And then we had teams of 20 people who are enrolled in the class come and do work installations at their projects.

And then we had a team of five apprentices who had been working with us for a year who acted as the crew leaders. So through all of that, the students paid some money, but not as much, and the landowners paid money and the apprentices got a little money and exchanged education. We got paid for the for the work. The landowner got a low cost installation. It worked out for everybody, got a bunch of things done and so I would call an example of the kind of more invisible layers of how permaculture work is done.

But of course, it was integrated with the visible as well, the installation of permaculture systems.

So in this case, as with the chickens and all those yields, mulberries, manure, eggs, no invasive plants, there were multiple benefits from the same well-designed action, the benefit of the land owner getting a permaculture design and work on their home site.

The apprentices got some experience designing and working with people in applying permaculture design. The people who wanted to learn permaculture less expensively and didn’t care about a certification, they just wanted to learn it. They got to do it for less money and then get hands on.

Yes, and the permaculture trainer got income and all kinds of yields.

We actually sat down and listed like 20 different benefits and yields that we received from it at the end of it.

Thank you. Thank you for that example.

Yeah, you’re welcome.

Can you give any other examples, if you wish, of social permaculture design and economic permaculture design?

Well, I think where I’d like to take it, is how we got into Co-operate WNC and the mutual aid work, because you said there’s this thing in systems thinking in which permaculture, by the way, is, of course, sister of or some kind of relative of systems thinking, which everything we just described is systems thinking. It’s not thinking of people or plants or anything as an isolated element. But how does it all work together in a food web?

Well, let me just ask you something before you go to that where you were going. So that our listeners can get a picture of a system, it’s not a thing or an action. It is a collection of things and actions that together give you more as a group or as an individual than you would have had if you had any one individual thing or action. And one example I’d say is our chicken patrollers around the edge of the property. And another example are those apprentices, the landowner and the permaculture students in the permaculture training all benefiting from that design. So it’s applying design to things and actions for great beneficial results to everyone involved.

Yeah, OK. Yeah. And and one of the one of the kind of facets of systems is understanding nested systems, which means which nested means like a like an egg nesting and in, in a nest. But there are different scales of systems that are inside of each other like a common ways to think about it is an organ in my body. My lung is a nest, is a system in itself. It’s also part of my whole body, which is a system.

And then I am part of my family, which is a system and also Earthaven, which is a system, and also the United States and there are other levels between that and so and inside a lung, inside a set of three lungs and trachea are smaller systems, the alveolar system. And the blood exchange system. So little systems are nested inside bigger systems. And the whole thing is a pattern of systems. And for those who look at strange, amazing mathematical art like fractals…

So you were, I think, going to tell us a little bit more about how you came to be fascinated with, intrigued by and wanting to create Co-operate WNC.

Yes.

And and that’s about kind of understanding scale and nested systems, which is that I started to see through my permaculture work that I was saying earlier, there’s this fragmented society in the U.S. And many people unwilling to make the short-term changes that could be called sacrifices that are necessary for a long term kind of wellbeing. And I see that fragmentation as the single biggest barrier to the type of transformative ecological healing and other kinds of healing that we need locally and and at the national and global scale.

And I really came across that in my permaculture work because I was usually working with nuclear families who hired me to do a permaculture design or installation and most of the students in classes, nuclear families and people would learn all these things. But the thing is, permaculture is a multigenerational project. And it’s a human transformation project. And it’s impossible to do as an individual or as a nuclear family in a meaningful way because we’re nested in these systems that are heavily weighted against it at every level. I discovered that I would do a permaculture design for a nuclear family, a couple, and we would come up with this 125 year vision for their property. But then they’re both working full time jobs and their parents live in other states. And besides, they don’t have enough support for their relationship because they’re living on a farm by themselves and all kinds of things in their personal lives would break down in their attempt to even enact something like that.

So I started to see that we needed support systems and a greater set of skills and culture around cooperation to have any chance at enacting the kind of grand vision of permaculture.

So what I take from what you just said is that the example of that couple on the farm by themselves with their parents in other states and they each have a full time job, is that even though they paid for, got interested in and were probably excited about the 125 year plan through multiple generations of how to grow and develop multiple interacting nested systems for higher yield on their farm, they didn’t have the time. They didn’t have the extra people. They didn’t have the other generations.

They couldn’t possibly predict what would or wouldn’t happen in the next 60, 70, 80, 100, 125 years. So without the nested social support system already in place, how can they possibly do that? Permaculture design.

And that’s what you noticed and got you going on this.

Yeah, and then looking around us and at the history of humans and human cultures, what stands out is this. Experiment in nuclear family living, in isolated living, is a very recent experiment. It’s enabled by the industrial revolution and it’s basically failing and having dramatic impact on humanity through.

You can see it through depression, rates of depression. You can see it through all kinds of social breakdown. And so, but alternatively, if you look at the history of cooperation and how we’ve organized ourselves in communities at different scales for for our entire existence as a species, that’s how we survived. That’s how we dealt with the complexity and unexpected twists of life. And so I started studying that. And then I had this one particular visit that was really formative for me. I had the honor of visiting this group of indigenous people in northern Oaxaca, in Mexico and north central Oaxaca, with the Mixteca people in Yukuyoca, which is a village that’s a part of a group of 12 villages with a multi thousand year intact mutual aid culture living in the same place for thousands of years through the Spanish invasion.

And there I got to I was actually there studying kind of agroecology practice, milpa farming. But what I saw, I got more than I bargained for, was that they had this very intact type of cooperation and mutual aid, a whole vocabulary around mutual aid like like the Inuits have around snow, all the words for different snow. These folks have 10 or 12 words for the different organs of mutual aid and they’re in their culture. And one of the things they were doing was they were starting from seeds and planting 700,000 trees a year among this cluster of 12 villages with 75 to 150 people in each village based in their own cooperative financing of the project to reforest this desertified landscape around them that had been created through Spanish logging of the area. And so when I saw that and all the ways they cooperated, not just on farming and agroforestry, but also on taking care of the elderly and the children and training people for schooling and dealing with health issues, I was blown away and I was like, wow, this is a tangible example for me of what mutual aid culture could look like.

That was in early 2017. I came back from that with with a sense of clarity and determination around, I think this is the direction we need to go, in our own place in society.

If I had had that experience, I would have been blown away, too. Did you say 700,000 trees a year, 150 people in 12 villages of all different ages because it’s multigenerational villages?

Yeah, yeah. And they were increasing the rate when I was there, so it’s probably more by now.

So did you see those trees doing what trees do when planted in desert landscapes, which is changing the culture, changing the moisture level and then acting as shade nurse plants for little plants to grow under their shade and then re populate the area with actual growing plants?

Yeah, we could really geek out on that. I saw some amazing things in that regard. Really quickly, it was part of a 30 year farming cycle, land management cycle they had, where they were planting alder and pine trees and then they would grow those for 30 years. Alders or nitrogen fixers, which improve the soil, and then they would cut the trees down and then grow milpa, grow corn, beans and squash, anapolis cactuses, edible cactuses, in those spaces, and agave.

And then after some time, they would come back and plant trees in that same spot. So it was a long-term mosaic of landscape management. And I got to put my arm into the soil in one of the places they had planted 27 years before I was there and there was there was like ten inches of dark black topsoil there, whereas 100 feet to the west there was no topsoil. It was literally limestone with a few cactuses. So I got to see the impact of that planting, it was very impactful.

So you came back to the U.S., fired up with the idea of, OK, what can we learn from this and how can I help this happen?

Yeah, exactly. And I’ve been reading about the history of of cooperatives and mutual aid in the U.S., which is a very grand history for anyone who wants to dig into that. And it’s the birth of the credit union movement in the U.S.. The birth of the unions in the U.S. Came out of mutual aid societies. And I said, wow, there’s a lot here. And specifically around farming and agriculture. There’s there’s a huge history in the U.S. and everywhere of cooperatives in organizing agriculture and organizing farming systems between communities, the Grange in the U.S. is an old mutual aid society that focused on farming. So yeah, and that’s where Co-operate WNC came came from. As I said, let’s make these linkages between the economics and getting beyond nuclear families and the social situation that we’re in, including institutionalized racism. Let’s make the connections between those things and ecological healing earth care and agroecology systems with physical stuff that permaculture does.

Let’s make those connections more visible and more explicit and use cooperation and mutual aid, financial arrangements and grassroots organizing to support the type of long term permaculture work that we that we know we need to do.

What kinds of projects is Co-operate WNC taking on here in this region of Western North Carolina?

Well, we’ve got several really exciting things going on. You know, one of the big things is, we’ve forgotten this stuff as a culture, even about cooperation, so, again, it’s hard to imagine what we can’t see. And so a lot of what we’re doing at this time is some foundational education and training around cooperative history and possibilities and tools and techniques, now serving a lot of educational gatherings, learning circles, we call them. But we do have several programs that are actively doing stuff, including community savings pools development, which is a cooperative financing technique from from New Zealand.

There are variations around the planet. But in this one, 15 to 25 people get together and pool their savings and then make proposal-driven loans to each other for starting a farm or starting a business or paying off debt or paying the down payment on a house, different things like that. So it’s a way of cooperative refinancing stuff.

Does that mean the 15 or 20 people create their own little tiny bank and they are the ones who invest in it and fund it, and they’re the ones who can get a loan from it with each other as the people who help decide which things we’re going to fund. And then when they pay the loan back, they’re more likely to really want to do so because it’s peers and colleagues who loaned them their own money.

Yeah, it’s kind of informally like that. We are using an actual established bank to hold our money, but then it acts that way. We get to choose among ourselves what we lend money to with zero percent interest to. So far we’ve gotten three of them going and including one Earthaven and there’s a staff person, part time staff person who is helping to train people and has developed a training program for that.

And they have over 120 of them going in New Zealand. So we have some mentors over there who we’re talking with and learning from. And so that’s really exciting. And that ties into a lot of this stuff because that was a big barrier I ran into in permaculture work I was doing was, how do you finance all the good ideas? And here’s one way, right? So that’s one of our programs.

Another one is the WNC Purchasing Alliance, which is a cooperative bulk purchasing initiative that is connecting up different organizations and community groups to bulk buy all kinds of things that we need – foods or equipment, environmentally friendly cleaning supplies, farming equipment and supplies to get the costs down, but also to allow us to direct money towards locally owned producers and businesses.

So it’s a powerful way of kind of changing some of the economic dynamics.

So does that mean you’re doing the stacked functions of many different things coming in and many different benefits going out, which is part of permaculture design, as I understand it, so that people are putting money in to helping local businesses provide them with cheaper goods because they’re bulk there, but in bulk, the volume discount and distributing these goods among the very people who’ve been funding this? So they’re buying, but in a group, what they need and helping local businesses?

Yeah. Plus the connection socially of getting to know these other people and finding some friends and colleagues and allies.

Yeah, that’s huge. That last thing is the relationships. And that’s a big summary of everything we’re trying to do is to take things away from the transactional type of of economics that the industrial economy demands of us, where we treat other people or communities like mechanisms for our own devices, like buy and sell.

And we don’t care about you as a person and move that into relational economics, where every economic transaction becomes an opportunity for deepening trust and relating for other types of working together along with the economic transaction.

It sounds like what this is doing is recreating connections between generations and between neighbors, which is maybe how humans used to live before the relatively recent invention of giant cities, suburbia and the nuclear family that you alluded to before, to sew up the ragged sleeve, I’m quoting Shakespeare here, of a frayed sleeve of culture ,to reweave it, it sounds like.

Yeah, I think we are trying to do that.

Well, would you let our listeners know how they can learn from you through soil? I think you do offer various different kinds of classes online and in person through the SOIL organization.

Yes, we’re working together to put several different classes together related to agroforestry and to cooperative agriculture and cooperative organizing. So check out the SOIL website at schoolofintegratedliving.org for that and also for Co-operate WNC. We’re a nonprofit mutual aid network and that’s www.co-operatewnc.org. And check out our programs there and you can sign up for our newsletter as well.

And just one more word on that, which is Earthaven is my is my own personal greatest training ground for cooperative living because because we’re doing it here is mutual aid at different skills and in different ways. And so to be able to be here and learn those lessons in a day to day way and then apply them to a larger social context has been a real honor and gift.

Thank you so much then.

Thank you for listening. Please visit our website at Integratedlivingpodcast.org and sign up for our newsletter so you know when new podcasts are released. You can also browse the School of Integrated Living upcoming online and in-person class offerings. This podcast is produced by the Culture’s Edge School of Integrated Living at Earthaven Ecovillage in Western North Carolina. Have a great day.